The Monday, October 26, 2020 issue of Billboard Country Update led with an article about “Latinx Country [being] Poised for a Rebound.” The article opened with a statement about how the industry has addressed diversity, pointing to an influx of Black artists (name-dropping the four Black men signed to a major Nashville label) and an increase in airplay for female artists, and reflected on how the new duo Kat & Alex might end a more than 20-year gap since a Hispanic artist had a Top 10 country single. Not only are none of these points a sign that the industry has addressed diversity, but they also glaringly overlook the existence of Black, Indigenous, Hispanic women in the genre. As one individual on Twitter stated about the article, “I kept reading just because I thought they’d have the decency to mention Star de Azlan, but nope, not even that.” While de Azlan might not have had the chart success of Rick Trevino (the last Hispanic artist to achieve a Top 10 country single), she was the first Hispanic women to sign to a major Nashville label (Curb in 2007) and her debut single “She’s Pretty” peaked at #51 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart in 2008.

Star de Azlan isn’t the only Hispanic woman that has been signed to a major label. Although she didn’t speak openly of her Mexican heritage during her time on a major label, Leah Turner was signed to Columbia Records from 2013 to 2014. Her debut single “Take the Keys” peaked at #37 in 2013 – the highest charting single by a Latina country artist in the history of the industry. But Leah Turner wasn’t able to fully embrace her heritage earlier in her career and it’s not really hard to figure out why that might be in an industry that has yet to embrace, support or develop a career for a Black, Indigenous, Women of colour in country music. Turner spoke recently about how she is “standing in her second chance now” with her new single “Once Upon a Time in Mexico”, through which she embraces her heritage, bringing Hispanic culture into country music.

Discussions of diversity within the industry inevitably point to the chart-success of the few Black men that have been allowed to participate in country music as though that is some marker of progress within country music, but continually overlook the industry practices that have sidelined and blocked opportunities for Black, Indigenous, Women of colour (hereafter as BIPOC).

Just one week before the abovementioned Billboard article was published, I was asked to participate in a panel on gender representation at a Music Business Association conference called Driving Change. The panel spotlighted groups that have developed initiatives to support women within the industry over the last seven years, and I was asked to share data that would delve into issues of representation. A short timeframe, to be sure, but it brings us back to the final year that Leah Turner was signed to Columbia Records and the launch of Mickey Guyton’s career with the release of her debut single “Better Than You Left Me” in 2015. This timeline, then, affords us the opportunity to look at a period in which two BIPOC women were signed to a major Nashville label – a first in the industry’s history. It was thus imperative that my presentation highlight racial and gender inequities so that the conversation can discuss core systemic issues that plague the industry. Though brief, my presentation highlighted the exclusion of BIPOC women on country format radio and their absence on five of the major Nashville-based label rosters. I ended my talk by focusing on the ways in which the industry’s practices can be seen as a form of cultural redlining.

A note on the colour-coding schemes of the graphs below. SongData reports typically use grey for male artists, plum for female artists, yellow for male-female ensembles, and brown for gender non-binary artists. For this study, I used lighter and darker shades to represent white and BIPOC artists. I aimed to show both racial and gender representation within every graph, which is why this particular coding scheme was used. As will be seen below, there is such a small representation that the darker shade is needed for visibility. A lighter colour would render their participation in the industry invisible in these graphs. Within the category of BIPOC artists, I include bi-racial solo artists, Latinx artists, and multi-racial ensembles. I will provide detail on what this means for the graphic representation where needed.

Presentation slides can be accessed here.

Representation on Radio

As noted in my 6-month check-in on representation in country radio in 2020, there has been an increase in spins for songs by women and an increase in the amount of #1 songs by female artists this year. But, as I have been warning in my bi-monthly updates throughout the year, in that same period only a handful of songs by women were added to station playlists – nine for women and thirty-eight for men. This resulted in a deficit of songs by women in the backend of the chart until June/July, and we’ve seen the consequences of this: the declining number of songs in the Top 30 from a high of eight in March down to a low of one song by September.

What is most critical to understand is that these advancements, marginal though they may be, reflect opportunities for white women in the industry. What has been most disconcerting, though certainly not surprising for the country music industry, is the continual absence of BIPOC women on radio. Despite receiving a standing ovation at Country Radio Seminar in February 2020 and releasing three critically acclaimed singles, Mickey Guyton’s music has been ignored by country format radio.

As shown in the first figure, between 2014 and 2019, female artists received an average of one million spins a year, hovering around 9% of the annual airplay for all songs (currents, recurrent and golds). While there has been an increase overall this year, 2020 is of course not over and (as shown in the following graphs) airplay for songs by female artists is declining yet again so it is very likely that the annual percentage will be closer to 12% by end of year. You can see by the volume of spins per year, that there are not that many more spins in 2020 than in the years preceding it.

BIPOC men have seen an increase in airplay for their songs over this period. Although the period average is 5.1%, spins for songs by BIPOC men and multi-racial male ensembles increases from 2.5% in 2014 to a high of 8.9% by 2019. This year, they average 7.3% of the airplay, but there remains a few months to accumulate more spins. The majority of these spins have been for songs by Dan + Shay (Dan Smyers has Japanese heritage) at 37.1% of the spins for BIPOC men. Kane Brown comes in a close second with 32.5% of the airplay, Darius Rucker with 17.8% and 12.0% for Jimmie Allen. The remaining 0.6% of the spins for BIPOC men was distributed between Blanco Brown, Lil Nas X, Neal McCoy, Sundance Head and eight non-country artists. Both Dan + Shay and Kane Brown rank within the top 20 artists based on total accumulated spins over the last seven years – a list almost entirely make up of white men, save for Carrie Underwood who ranks at #16 on the list.

More critically, this figure presents a picture of the distribution of spins for songs by BIPOC women, which averages 0.4% – increasing from 0.1% in 2014 to 0.4% in 2020. In this six-year period, the only airplay for BIPOC women went to Leah Turner, Mickey Guyton , and multi-racial female ensemble Runaway June (whose lead singer Naomi Cooke has Native American heritage). Not surprisingly, Leah Turner’s final year of airplay was in the first year of this short period (her final year with Columbia), with spins for both “Take the Keys” and “Pull Me Back”. Mickey Guyton had airplay throughout this period, but her highest year of airplay was in 2015 when “Better Than You Left Me” debuted and climbed the charts. Only Runaway June has received support from radio, accumulating 250,000+ spins between 2016 and 2020. Indeed, the dark plum line is mostly spins for their songs in this five-year period, especially in 2019 at 1.0% of the annual airplay. In addition to these BIPOC country artists, over the last five years, songs by Camilla Cabello, Cardi B, Mariah Carey, H.E.R., Alicia Keys, Lizzo, and Cece Winans have received some airplay on country format radio.

Gone West (whose member Justin Kawika is native Hawaiian) is the only multi-racial male-female country ensemble to receive airplay in this period – registering the majority of their spins in 2019 and 2020. Spins for their songs (“Gone West”, “What Could’ve Been”, “Slow Down” and “Confetti”) registered 0.2% of the annual airplay in 2019 and 0.4% in 2020.

Drilling into 2020 so far (as seen in the first figure in the carousel below), we see that there has been an increase in spins for songs by women from 12% of the weekly airplay up to almost 18% by mid-April, and then back to 12% by the end of September. How does this track when we consider diversity?

The second figure in the carousel shows that white male artists come out on top, with an average of 77% of the airplay in 2020. When combined with the airplay for white women (14.8%) and male-female ensembles (1.9%), an average of 94.1% of the airplay has been for songs by white artists. The remaining 5.9% has gone to BIPOC artists: 5.8% for songs by BIPOC men, and an average of 0.1% for songs by BIPOC women. I reiterate, despite releasing three powerful and critically acclaimed songs, one that programmers at CRS championed and requested personally, Mickey Guyton’s music is not being played. …at least not when audiences can hear it.

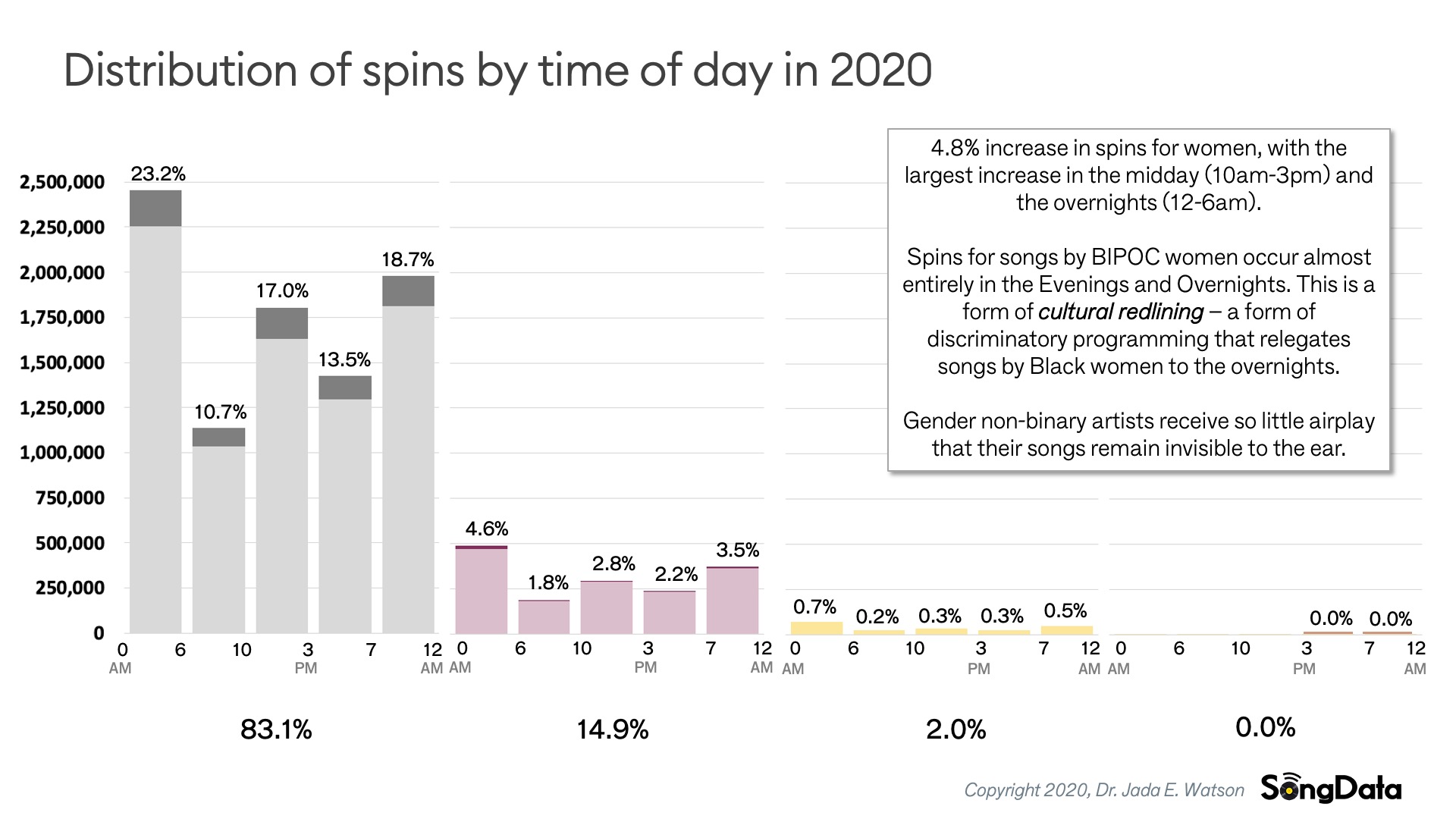

When looking at how this tracks through the 24-hr period (the final figure in the carousel), we can see more clearly how those spins have been distributed over the course of the 5 dayparts in radio programming, from midnight to midnight (left to right). The majority of the 4.8% increase in spins for songs by women have gone to the midday (+1.6%), evening (+1.1%) and overnights (+1.1%), with a negligible increase in the peak hours of the morning (0.6%) and afternoon (0.4%) dayparts. Perhaps more critically, as can be seen in this final carousel figure, the majority of spins for BIPOC women have occurred in the evenings and overnights. While this is true for both Mickey Guyton (30.5% and 35.5%, respectively) and Runaway June (49.3% and 22.2%, respectively), the trio’s songs have received 41 times more airplay than Guyton’s, who has yet to reach a combined 1,000 spins for her three current singles. While new songs are typically added in the overnights first, a historic practice at radio, this is a form of cultural redlining that avoids investment in Black women by relegating their songs to a daypart with no audience.

It is critical to note that LGBTQ artists are also absent from this format. With just two openly gay country artists receiving airplay in 2020 – neither of which with enough airplay to chart on terrestrial, LGBTQ artists remain invisible on country format radio. It is worthy to note that one of these artists is the The Highwomen supergroup, which includes singer Brandi Carlile, a group that has been embraced by Sirius XM’s The Highway. Like the results for BIPOC artists, LGBTQ and gender non-binary artists (in general) and country artists (specifically) are significantly disadvantaged within country music culture – and transgender artists are absent.

Representation on Nashville labels

Radio airplay is only part of the industry’s cycle. One of the biggest complaints from radio is that they do not have enough songs by women to program. So in an industry that depends on having songs by signed artists to promote, it is imperative to look at representation on label rosters to understand the deficit of songs by white and BIPOC women on radio.

Over this seven year period, 264 artists have been signed across these five labels. Not surprisingly, the majority (65.9%) are white male artists, 23.9% are white female artists, and 4.5% are white male-female ensembles – making up 94.3% of the artists signed. Just 5.7% of those signed to these five labels are BIPOC artists: 4.2% male artists, 1.1% female artists, and 0.4% male-female ensembles. Only one BIPOC woman and one multi-racial female ensemble are currently signed to a major label.

Looking at representation on these five rosters over the last seven years, there has been an increase in the number of women signed, from 28 women in 2014 to 39 by 2020. But the signing of male artists – more specifically, white male artists – means that the representation of women signed to these five labels has increased just one percentage point. Indeed, white male artists have been signed at such a high rate this year alone that the increase in representation for women is negligible. With the exception of a drop to one BIPOC woman in 2015 (after Leah Turner was let go from Columbia Records), there has been an average of just two BIPOC women signed to a major Nashville label over the last seven years.

Looking at each label individually, we see that Big Machine and Warner have not had a BIPOC woman on their roster since at least 2014 (if ever), while Sony had Leah Turner (via Columbia) in 2014 (and Crystal Shawanda before her on RCA from 2007-2009), Broken Bow has had Runaway June on its roster since 2016, and UMG (via Capitol) has had Mickey Guyton on its roster since 2011. While Runaway June had a #8 hit with “Buy My Own Drinks”, neither Leah Turner nor Mickey Guyton has had a single crack into the Top 30 of an Airplay chart. The only solo BIPOC women to have a song peak within the Top 30 are Linda Martell, whose “Color Him Father” peaked at #22 in 1969 and Crystal Shawanda, whose “You Can Let Go” reached #19 on the Mediabase chart and #21 on the Billboard chart in 2008.

Although white women make up nearly a quarter of the artists signed to a major label in Nashville, less than 10% of them have enough support to achieve success and visibility within the industry. Between 2014 and 2020, 478 songs peaked in the Top 20, only 48 of which were by women (10.1%) – 40 of which (8%) were by a female artist signed to one of these five labels.

Perhaps more concerning is that these 40 songs are recorded by just 17 of the 66 women signed to one of the five major Nashville labels. This means just 25.6% of the signed female artists (or, to put it another way, 6.5% of the artists signed overall) have had enough support to push their songs into the Top 20. Only one of these 40 songs was by a multi-racial all-female ensemble (0.2%). None of these songs have been by a BIPOC woman.

Given that airplay and chart success govern eligibility for industry awards, it starts to become clear when seeing these numbers why white women are underrepresented at country industry award shows and BIPOC women remain completely absent.

Cultural Redlining

Radio airplay doesn’t just impact representation in one sphere of the industry – it impacts the entire ecosystem and, over time, ripples across the industry until there are representational issues at all levels of activity. The carousel of graphics below offer a visual representation of the cyclic relationship between actors within the industry and its impact on artists. The first graphic outlines industry actions and relationships between agents within the ecosystem, on which is layered the consequences of those actions on the careers of artists and long-term health of the ecosystem in the second graphic. It doesn’t matter who initiates the change among the industry actors on the right hand of the cycle, because agents are always responding to actions/practices of others in the system.

The actions within the industry are typically based on historical practices – and data resulting from them – as a means to decision making. The industry continually uses the past as a way to define the present and build toward the future. As a result, the foundational practices that were institutionalized in the early days of the industry through racial segregation and gender discrimination have become a self-fulfilling prophecy (the final graphic in the carousel). Decreasing the number of women in one realm of the industry eventually leads to a decline across all other areas. While there has never been a point in the history of the industry in which men and women have equitable access to resources and opportunities, since the early 2000s (after the passage of the amendments to the Telecommunications Act in 1996), the number of songs by women have declined drastically on radio, resulting in fewer songs by women on the charts, which inevitably impacts the ways in which labels sign and promote female artists and the ways in which publishers sign and discourage writing for and by female songwriters. This lack of exposure results in diminishing opportunities and resources for women, which means that very few women meet the minimum threshold criteria to be eligible to walk on a red carpet at events, to sing their music on an award show stage, to be nominated for an industry award and, over time, to be considered for tributes and honours within the industry – including the Country Music Hall of Fame (of which just 14.1% of inductees are women).

To be clear: this is the reality for white women.

This cyclic relationship doesn’t account for Black women, Indigenous women, and Hispanic women who are not afforded the opportunity to participate in this industry space. Not only was Mickey Guyton the first Black women to be signed to a major Nashville label in 2011, but she was the first ever to be nominated for an industry award with her 2016 ACM nomination for New Female Artist of the Year, and was the first Black woman to perform her own music on the ACM stage in September 2020. The CMA Awards have yet to have a Black female nominee for one of its awards. There are no Black women in the Hall of Fame. Just 1.4% of the inductees are Black men, who are also marginalized within the industry (and tokenized or presented as an anomaly, as evidenced in the aforementioned Country Update article published this week). For BIPOC women to be eligible for one of these awards, it’s not just the criteria that need to change, but the racist practices that govern how the industry functions as well.

What we see here is a form of cultural redlining, which relegates the music of BIPOC artists to the margins of the industry. While the concept of “redlining” has historically been used to understand how customers have been denied policies based on race and ethnicity, Safiya Umoja Noble has recently applied this term to our modern data-driven era, looking at the ways algorithms directly or indirectly use criteria like gender, race, ethnicity (and more) to make assessments (or recommendations). Much of her writing on technological redlining and algorithm/data discrimination resonates in cultural spheres, where contemporary decisions are based on historic (often racist and sexist) data. So, in an industry built on racial segregation and gender discrimination, one that is obsessed with chasing data – in the form of sales, spins, charts, streams, award nominations, etc. – their historic exclusion means that there is no data to support the development of artistic careers of BIPOC women in country music.

Data serves to justify and maintain industry practices.

Or, as Sara Ahmed states, “this is how inheritance is reproduced.” The white patriarchal industry has “inherited decisions that made these exclusions for [it], without [it], decisions that mark edges, marking out where [it does] not have to go.”

Critical Writing on Black Women in Country Music

- Rissi Palmer, “Color Me Country” on Apple Music; presented bi-weekly on Sundays at 7pm (edt).

- Olivia Roos, “Country Music’s Reckoning: Black Women Forge Their Own Path in Whitewashed Industry,” NBC News, October 15, 2020.

- Andrea Williams, “Mickey Guyton Stands Strong on her New EP Bridges,” Nashville Scene, September 17, 2020.

- Andrea Williams, “Why Haven’t We Had a Black Woman Country Star?” Nashville Scene, August 5, 2020.

Radio Airplay

- “Country Radio Has Ignored Female Artists for Years. And we have the data to prove it.” NBC News Think, 17 February 2020.

- “Six Months of EqualPlay: An Update.” SongData Reports; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 26 July 2020.

- “Inequality on Country Radio: 2019 in Review.” SongData Reports; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 17 February. Prepared in partnership with CMT’s Equal Play Campaign. Associated Brief available.

- “Gender Representation on Country Format Radio: A Study of Spins Across Dayparts.” SongData Reports; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 6 December. Prepared in consultation with WOMAN Nashville. Report Brief available.

- “Gender Representation on Country Format Radio: A Study of Published Reports from 2000-2018.” SongData Reports; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 26 April. Prepared in consultation with WOMAN Nashville. Report Brief available.

Streaming

- “Reflecting on Spotify’s Recommender System.” Keeper of the Flame (blog), October 2019.

Industry Recognition

- “Inclusion and Diversity in the ACM Award History: A Study of Nominees and Winners, 2000-2019.” SongDataReports; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, May 2020.

- “Gender Representation of CMA Awards: A Study of Nominees and Winners, 2000-2019.” SongData Reports; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, November 2020.